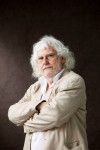

Aonghas MacNeacail by Murdo Macleod

Skyeman Aonghas MacNeacail is an award-winning poet in Gaelic, English and Scots, songwriter in folk and classical idioms, journalist, broadcaster, translator and occasional actor. Laoidh an Donais Oig (Hymn to a Young Demon) appeared in 2007, and his New and Selected Gaelic poems, Deanamh Gàire ris a Chloc (Laughing at the Clock) is newly published and was shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year. He will travel to Cairo this week for the Edinburgh World Writers’ Conference to respond to Tamim Al-Barghouti’s keynote address on ‘Should Literature Be Political?’

EWWC: You’re visiting Cairo this week to take part in the Edinburgh World Writers’ Conference. Do you have any particular affinity with or interest in the Arab world?

AM: I am a passionate news addict, and describe myself as a non-practising journalist (I’m still a member of the NUJ though). But coming from my own background of a culture under threat [as a Gaelic speaker and writer] has made me interested and concerned with the issues surrounding, for example, the Kurds – a culture whose identity has been extrapolated by those surrounding it. But I am inevitably drawn to be interested in the plight of the Palestinians as a people without a state. To put myself in perspective, I belong to a culture, Scots Gaelic, which has less than 100,000 speakers, though now with a thriving education system through the medium of the language (so there’s hope).

I both curse and bless the Arabs for algebra – and all the wonderful things we gain from it! So while I don’t have a specific academic or journalistic interest, I have a strong general interest in and personal awareness of what’s happening in the Arab world.

EWWC: In terms of cultural identity, language is always going to play a major part. For you is it THE major part?

AM: Yes, for me it is. The language in a sense defines who I am. I am trying to get a campaign going in Scotland based on the premise that ‘I am not an adjective’. I have come to the stage where I am tired of being identified as ‘Gaelic Poet’. I’m proud of my Gaelic background and my ability to express myself in Gaelic. But I’m also a poet in English and indeed I’m also a poet writing in Scots; and sometimes it’s the case that an adjective can be used as a box. So you live with a divided loyalty to your own culture in that sense; you’re proud of it – and yet you don’t want to be defined by it.

EWWC: At the Conference in Edinburgh you were, I think, the only representative there for Scots language writing. Did this make your participation a no-refusal? Is it sometimes something of an albatross?

AM: Certainly I was the only representative for Scots Gaelic, yes. I’ve been in that position so many times, you get used to it I suppose. You are aware that often you’re invited to take part as someone who represents the culture and who is not afraid to take a position.

EWWC: What questions do you think a World Writers’ Conference in 50 years’ time might address?

AM: I think I’m one of the last of the generation which is tied to the printed page. I’m toying with the idea of buying myself an ipad, and I don’t have an e-reader as yet. I’m still holding on to the book. We are very much moving into the electronic age and I think there are going to be huge changes. But people are always going to have tell stories, people are always going to have to sing, people are always going to have to recite.

I’m working at the moment on an extended essay on the life and the poetry of Nazrul [Kazi Nazrul Islam, 1899 – 1976], who’s the national poet of Bangladesh. He’s hugely popular in his own culture and, like Tamim [Al-Bargouti] – they are much closer to the oral tradition that perhaps British, European and American poets are. The poetic tradition I come from has until the 20th century essentially been oral. I have much too bad a memory to be an oral poet – I forget my own words! But I think there’s a chance that oral poetry will become much more pronounced, with people becoming more attuned to hearing and listening to poetry through the new media. Despite the fact that I can’t understand the language, listening to Nazrul read his poetry on YouTube it comes alive, because you can hear the rhythms, the sonorities, the tonalities – it’s really hypnotic stuff. You can match the sound patterns and the rhythms with the words, even if they’re not brilliantly translated – and suddenly it’s a different ball game.

EWWC:“Should the novel be political? I don’t believe in ‘should’ anywhere near art.” – Ahdaf Soueif, EWWC. What do you think?

AM: Should literature be political? No. It can be, it may be, even will be – but not ‘should’ – should sounds terribly Presbyterian! Poetry should be honest and reflect the world of the poet, and if the poet is engaged with the world around him then it has to be political in a sense – it can’t be otherwise.

One of my most delightful moments was being invited to a festival in Rome, which was held in the open air on the Capitol. In front of me was the Statue of the great Caesar, Marcus Aurelius, on his horse, and in the museum to the right the statue of the Dying Gaul (the last Celt!) – and I was there, reading my poems in Gaelic, a Celtic language, and saying ‘Caesar, we’re still here!’ That affirmation of keeping the language alive is very much a political act.

EWWC: And finally … If you had to be exiled permanently to one of the EWWC cities – Edinburgh, Berlin, Cape Town, Toronto, Krasnoyarsk, Cairo, Jaipur, Beijing, Izmir, Brussels, Lisbon, Port of Spain (Trinidad), St Malo, Kuala Lumpur & Melbourne – which would you choose and why?

AM: I have one ambition – to go south of the equator, I’ve never been. So I might play it safe and sayMelbourne, because of the lack of a language barrier. I might even meet a few Gaels there. My clan chief is in Australia!

(Above image of Aonghas MacNeacail© Murdo Macleod)